Every time a client sends a request to a server, such as a browser requesting a webpage or a frontend app calling an API, the server responds with a status code that explains what happened. These codes tell the client if the request was successful, failed, needs to be retried, or should be redirected.

This article explains what these codes are, where they appear, how they’re categorized, and how to simulate them during testing using Requestly.

What Are HTTP Status Codes?

HTTP status codes are three-digit numbers that a server sends back to a client to explain the result of a request. They are built into the HTTP protocol and appear when someone visits a website, calls an API, submits a form, or interacts with any HTTP system.

These codes act as short responses that tell the client what happened. Here’s what these codes mean in general.

- 1xx (Informational): The request was received, and the server is still processing it

- 2xx (Success): The request was successful and the response contains the expected result

- 3xx (Redirection): The client needs to take further action, like following a redirect

- 4xx (Client Error): The request was invalid, often due to bad input or lack of access

- 5xx (Server Error): The server failed to handle a valid request due to an internal issue

Where Are HTTP Status Codes Used?

HTTP status codes are used wherever systems communicate over HTTP. Originally built for the web, they now appear in APIs, mobile apps, proxies, CDNs, and analytics platforms.

Here are the key areas where status codes are essential:

1. Web Browsers

Browsers use HTTP status codes to decide how to handle web requests. These codes control what happens next, and you will likely see these during debugging in tools like Chrome DevTools.

- 200 OK means the page should load normally.

- 301 or 302 tells the browser to redirect to another URL.

- 404 Not Found triggers an error screen when the page doesn’t exist.

Also Read: What is a Browser? How does it Work?

2. APIs

In RESTful and GraphQL APIs, status codes represent the result of an operation. A 201 Created is used when a new resource is successfully created. A 400 Bad Request signals malformed or missing input, and a 401 Unauthorized indicates the user needs to authenticate.

Well-designed APIs consistently use status codes so frontend developers and users can understand and handle failures properly.

Also Read: What is API Testing? (with Examples)

3. Mobile and Web Apps

Even though many apps don’t expose HTTP directly, they still rely on it in the background. When a mobile app syncs data or fetches content, HTTP status codes are returned behind the scenes. These codes affect app behavior, such as showing error messages or retries when a 503 Service Unavailable is received.

Read More: What is Mobile App Security Testing?

4. SEO and Crawlers

Search engines like Google use status codes to crawl and index content. A 200 OK tells the crawler that the page is available. A 301 Moved Permanently helps transfer page authority. A 404 Not Found or 410 Gone signals that the page no longer exists and should be removed from search indexes.

5. Load Balancers and Proxies

Load balancers and proxies like AWS ELB, Nginx, and Cloudflare use HTTP status codes to manage and report request handling. These systems often generate codes when the backend is unreachable or times out.

- 502 Bad Gateway appears when the proxy receives an invalid response from the backend server.

- 504 Gateway Timeout means the proxy did not get a response from the backend in time.

Monitoring these codes helps identify infrastructure issues like downtime or failed deployments at the edge layer.

6. Monitoring and Logs

Status codes are logged automatically by web servers like Apache and Nginx, as well as most application frameworks. They are essential for tracking uptime, errors, and unusual behavior. A sudden spike in 5xx errors can point to a backend failure or deployment issue. Monitoring tools use these logs to trigger alerts and help teams respond quickly to incidents.

Read More: What is End-to-End Monitoring?

Categories of HTTP Status Codes

HTTP status codes are grouped into five categories. Each category tells you the type of response returned by the server. Understanding these groups helps you quickly determine what went right, what went wrong, or what needs to happen next.

1xx: Informational

These codes mean the server has received the initial request and is still working on it. They are used when the client is about to send a large amount of data, and the server wants to check if everything looks fine before continuing. This helps avoid wasting time or bandwidth if the server is going to reject the request.

You typically won’t see these codes on websites like Netflix or Amazon. But they are used behind the scenes in situations like uploading a large file or sending a video stream from an app to a server.

The 1xx HTTP Status Codes include:

- 100 Continue: The server received the headers and tells the client to send the body of the request. Common in file uploads.

- 101 Switching Protocols: The server agrees to switch protocols, like upgrading from HTTP to WebSocket.

- 102 Processing: The server has accepted the request and is still working on it, used mostly in WebDAV operations.

- 103 Early Hints: Used to preload assets before the final response arrives. Helps improve performance by sending resource hints early.

2xx – Success

These codes mean the request was successful. The server understood what the client asked for and completed the request as expected.

You see this when a page loads, a form is submitted, or an app fetches data correctly. For instance, every time you load Instagram or check your email, successful requests are returning 2xx codes in the background.

2xx HTTP Status Codes include:

- 200 OK: The request worked and the response contains data. This is the most common status code.

- 201 Created: Something new was created on the server, like a new user account or post.

- 202 Accepted: The request was accepted, but processing is not complete yet. Used for async tasks.

- 203 Non-Authoritative Information: The response is from a proxy or third-party source, not the original server.

- 204 No Content: The request was successful, but there’s nothing to return. Often used in DELETE operations.

- 205 Reset Content: Tells the client to reset the form or view after the request. Similar to 204 but with UI instructions.

- 206 Partial Content: Only part of the data was returned. Used for resumable downloads or media streaming.

- 207 Multi-Status: Used in WebDAV to return multiple status codes for different parts of a multi-resource operation.

- 208 Already Reported: Also used in WebDAV. Prevents repeating the same response for the same resource in a multi-status reply.

- 226 IM Used: Experimental. Indicates the response includes results of instance manipulations applied to the current instance.

3xx – Redirection

These codes mean the server tells the client to go to a different URL. This happens when something has moved or the server wants to redirect the client somewhere else.

This is used when you click a link and it quietly forwards you to another page. For example, when you visit an old product URL on an e-commerce site, it redirects you to the new version.

3xx HTTPS Status Codes include:

- 300 Multiple Choice: The request has more than one possible response. The user or client must choose one.

- 301 Moved Permanently: The URL has permanently changed. Browsers and search engines should update bookmarks or links.

- 302 Found: Temporary redirect. The resource is at a different URL for now, but the original one still works.

- 303 See Other: The response is available at another URI using GET. Often used after a form submission.

- 304 Not Modified: The client’s cached version is still valid. The server doesn’t send the data again.

- 307 Temporary Redirect: Similar to 302, but the method, such as POST, must not change during the redirect.

- 308 Permanent Redirect: Similar to 301, but like 307, it preserves the request method and body.

4xx – Client Errors

These codes mean there’s a problem with the client’s request. The server understood the request but couldn’t process it because something was missing, incorrect, or unauthorized.

You’ve probably seen these codes while browsing. For example, a 404 Not Found error appears when you try to open a broken link, or you might get a 401 Unauthorized error if you try to access your account without logging in.

4xx HTTP Status Codes include:

- 400 Bad Request: The server couldn’t understand the request due to invalid syntax or data.

- 401 Unauthorized: The request needs valid authentication. Usually triggers a login prompt.

- 402 Payment Required: Reserved for future use. Some APIs use this for paywalls or quota limits.

- 403 Forbidden: The client cannot access the resource, even with valid credentials.

- 404 Not Found: The resource does not exist at the given URL. Common for broken or mistyped links.

- 405 Method Not Allowed: The HTTP method used (like POST or PUT) is not allowed for the URL.

- 406 Not Acceptable: The server can’t return a response that matches the client’s Accept headers.

- 407 Proxy Authentication Required: Like 401, but for proxy authentication instead of direct access.

- 408 Request Timeout: The client took too long to send the request. The server gave up waiting.

- 409 Conflict: The request conflicts with the current server state. Common in concurrent updates.

- 410 Gone: The resource used to exist but has been permanently removed.

- 411 Length Required: The request is missing a Content-Length header that the server requires.

- 412 Precondition Failed: The server didn’t meet the conditions set in request headers like If-Match.

- 413 Content Too Large: The request payload is too big for the server to process.

- 414 URI Too Long: The URL is too long for the server to handle.

- 415 Unsupported Media Type: The server does not support the format of the data sent in the request, based on the Content-Type header.

- 416 Range Not Satisfiable: The client asked for a part of the file that’s outside its range.

- 417 Expectation Failed: The server can’t meet the requirements set in the Expect header.

- 418 I’m a teapot: A joke status code defined in an April Fools’ RFC, originally meant for teapots refusing to brew coffee. It is not used in real applications.

- 421 Misdirected Request: The request was sent to the wrong server. Primarily seen in HTTP/2 setups.

- 422 Unprocessable Content: The server understands the content type, but the data is invalid. This is common in APIs.

- 423 Locked: The requested resource is locked and cannot be modified. This status is mainly used in WebDAV-based systems.

- 424 Failed Dependency: A previous request failed, so this one can’t proceed. Used in WebDAV.

- 425 Too Early: The server is unwilling to process the request because it might be replayed.

- 426 Upgrade Required: The client must switch to a different protocol supported by the server, such as moving from HTTP to HTTPS.

- 428 Precondition Required: The server expects specific request conditions to be set to prevent conflicting updates or changes.

- 429 Too Many Requests: The client has exceeded the allowed number of requests in a given time window. This is typically used in APIs that enforce rate limits to prevent overload or abuse.

- 431 Request Header Fields Too Large: The request headers are too large for the server to process.

- 451 Unavailable For Legal Reasons: The content is restricted due to legal or copyright reasons.

5xx – Server Errors

These codes mean the server received a valid request but couldn’t complete it because something went wrong internally. The issue is not with your browser or app but on the server side.

You might have seen this during peak hours or when a site is under maintenance. For example, if you try to book a ticket during a big sale and the server crashes, you may get a 500 or 503 error.

5xx HTTPS Status Codes include:

These codes mean the client’s request was valid, but the server failed to process it correctly. These are server-side issues that developers or ops teams need to fix. They often show up during downtime, bugs, or configuration problems.

- 500 Internal Server Error: A general error with no specific message. Often caused by bugs, unhandled exceptions, or misconfigured servers.

- 501 Not Implemented: The server doesn’t recognize the request method or lacks support.

- 502 Bad Gateway: The server received an invalid response from an upstream service. This is common in apps behind load balancers or proxies.

- 503 Service Unavailable: The server is overloaded or down for maintenance. It may become available later.

- 504 Gateway Timeout: The server didn’t get a timely response from another system it was trying to reach.

- 505 HTTP Version Not Supported: The server doesn’t support the HTTP version used in the request.

- 506 Variant Also Negotiates: A server configuration error where content negotiation leads to a loop.

- 507 Insufficient Storage: The server can’t store the representation needed to complete the request.

- 508 Loop Detected: The server encountered an infinite loop while processing the request, typically in WebDAV-based operations.

- 510 Not Extended: The request needs more extensions that are not defined in the message.

- 511 Network Authentication Required: The client must authenticate with the network before accessing the internet. This is commonly seen on public Wi-Fi networks in hotels or airports.

How to Simulate HTTP Status Codes for Testing Using Requestly

Simulating HTTP status codes is crucial for testing how websites or applications respond to different server scenarios. You might need to simulate HTTP Status Codes to:

- Verify how a website behaves when a key API call fails with errors like 404 or 500

- Test code paths that depend on specific HTTP status codes returned by external services

- Validate user experience during server outages or resource unavailability

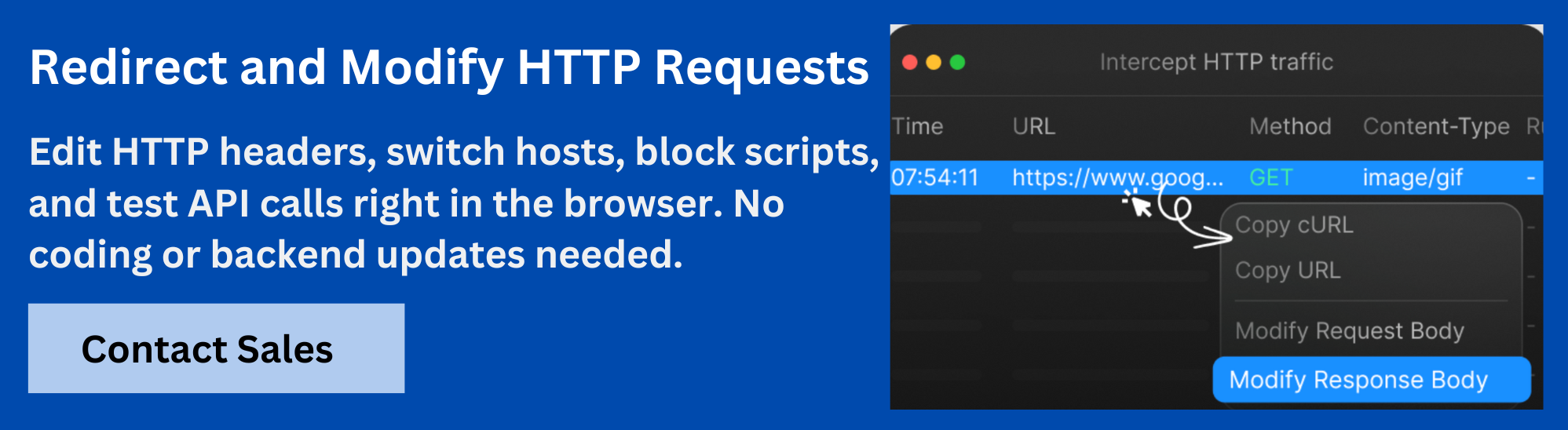

Requestly offers powerful features to modify responses and test error handling or fallback behavior without changing the backend.

Simulating Status Codes with the Requestly Desktop App

The Requestly desktop app provides a straightforward way to intercept and modify network requests, including changing response status codes. Here’s how:

- Download and install the Requestly desktop app.

- Launch the app and connect it to the browser where the target website will open.

- Open the website you want to test.

- In the Requestly interface, locate the network requests related to the feature you want to test. For instance, search for a request containing “GetHomeContents,” which loads the Hero Section.

- Right-click the chosen request and select the option to modify the response status code.

- Enter the desired HTTP status code to simulate, such as 404.

- Create the rule and reload the website to see how the page behaves with the simulated error response.

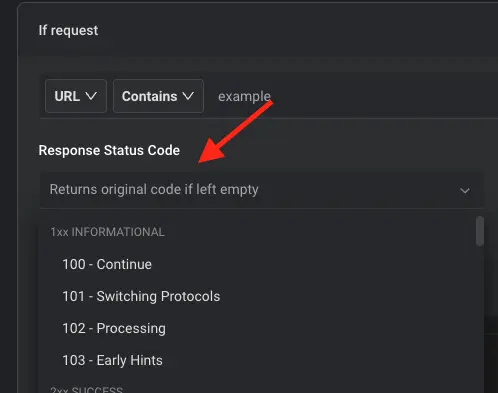

Simulating Status Codes with Requestly Browser Extension

For a lightweight alternative, Requestly’s browser extension can modify API responses triggered by XHR or fetch calls.

Steps to simulate status codes via the browser extension:

- Install the Requestly browser extension in your preferred browser.

- Navigate to the HTTP Rules section and create a new rule to modify API responses.

- Set a condition to match the request URL, such as URLs containing “/GetHomeContents”.

- Specify the status code to simulate, for example, 102.

- Save the rule and reload the site to observe the effects of the simulated status code.

Important notes:

- The extension can only modify responses for requests made via XHR or fetch. Other request types require the desktop app.

- Modifications made via the extension may not appear in the browser’s native developer tools due to technical limitations.

Conclusion

HTTP status codes define how a server responds to different types of requests. They help applications handle success, redirection, client mistakes, and server failures. To test these scenarios without depending on backend changes, you will need a client-side simulation. That’s where Requestly comes in.

Requestly lets you simulate these status codes without touching the backend. Teams can simulate status codes, handle test errors, and validate fallback behavior in real time without relying on server-side changes.